Jim Knipfel on Satire and Children’s Books

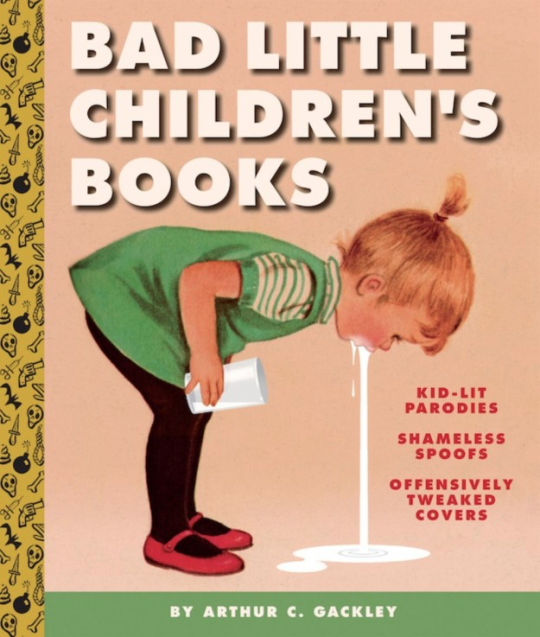

This past September, the Abrams’ imprint Image, which specializes in illustrated and reference works, published a novelty book entitled Bad Little Children’s Books by the pseudonymous Arthur Gackley. The small hardcover, which itself quite deliberately resembled a little golden book, featured carefully-rendered and patently offensive parodies of classic children’s book covers. Instead of happy, apple-cheeked tykes doing pleasant wholesome things, Gackley’s covers featured kids farting, puking, and using drugs. Others included children with dildoes and racially inflammatory portrayals of Middle Eastern, Asian, and Native American youngsters. The book was clearly labeled a work of satire aimed at adults, and adults with a certain tolerance for bad taste and crass jokes.

Upon its initial release it received positive reviews and sold fairly well. Then in early December, a former librarian named Kelly Jensen posted an entry on Bookriot entitled “It’s Not Funny. It’s Racist.”

“This kind of ‘humor’ is never acceptable,” Ms. Jensen wrote. “It’s deadly.”

Jensen’s rant circulated quickly across social media, and Abrams suddenly found itself besieged by attacks from the outraged and offended, who assailed Gackley for creating the book in the first place, and the Abrams editorial board for agreeing to publish it.

“There is a difference between ‘hate speech’ and free speech,” one outraged member of the kidlit comunity wrote on Facebook. “In the same way, you cannot yell ‘Fire!’ in a crowded theater just because you feel like it. This book was in very bad, insulting, racist taste, and designed to look like a children’s book. How is that a good idea? Children are too young to understand this as parody. If it’s for adults, why is that even funny? Oh, I guess if you are a racist you would think it’s funny.”

Another tweeted, “Sounds like something that should’ve been completely ignored and removed before it hit the shelves. Just because we have the freedom of speech, it can be taken way too far.”

Still another confused and enervated soul wrote, “Argue all that you want, but this particular book was for children yes? Or no? If it was, does that mean we should allow and subject young children to gratuitous violence, gore and pornography? And what age is it acceptable? Does this mean we have to start putting PG-14 on printed material and make it mandatory because certain writers can’t conduct themselves with a moral scale?”

Another angry reader summed it up quite simply by posting, “Freedom is bullshit, literally.”

[Note: As much as possible, the spelling, punctuation and grammatical errors which peppered the above posts have been corrected here for the sake of simple comprehensibility.]

Although Abrams initially stood by Gackley and the First Amendment right to offend, and had received the public support of several anti-censorship organizations, by December tenth the noise had simply grown too shrill. Mr. Gackley, maintaining to the end his intentions had been grossly misinterpreted, admitted there was no way to salvage things, and asked that Abrams not reprint the book. In a statement, Abrams announced they would be complying with his wishes. Although Bad Little Children’s Books was not banned in any official capacity, it had all but completely vanished from online booksellers within a few days after the announcement. Used copies, while available, are now selling for outrageous prices.

At the same time that this was happening, there were also calls to ban the (real) children’s books When We Was Fierce and A Birthday Cake for George Washington. The invented slang used in the former was interpreted as racist by some parent groups, and the latter was attacked for its historically inaccurate portrayal of the daily lives of slaves on Washington’s estate. Meanwhile, a mother in Tennessee led the call to pull Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks from the local school system. The New York Times bestselling biography, which concerned a Baltimore woman whose massive cervical tumor had become the invaluable source of several generations worth of cell lines used by cancer researchers, was being taught in local high schools as a means of educating students both about cancer and about racial issues within the medical community. The Tennessee mother calling for its removal, however, found the book pornographic.

Point being, I guess, that certain sectors of the population harbor an insatiable, even desperate desire to be shocked and offended by something they’ve read, seen, or even heard about, and the drive to ban these things (made much easier with the advent of social media) will likely always be with us. But back to the Gackley for a moment. Reading through the enraged postings aimed at Abrams, a number of the offended make the point that they are not attempting to censor, but are merely exercising their own First Amendment right to criticize. That’s fine and understandable. But the crux of the matter is that these people would be much happier if the book never existed in the first place, and considered Abrams’ decision a glorious victory for their cause.

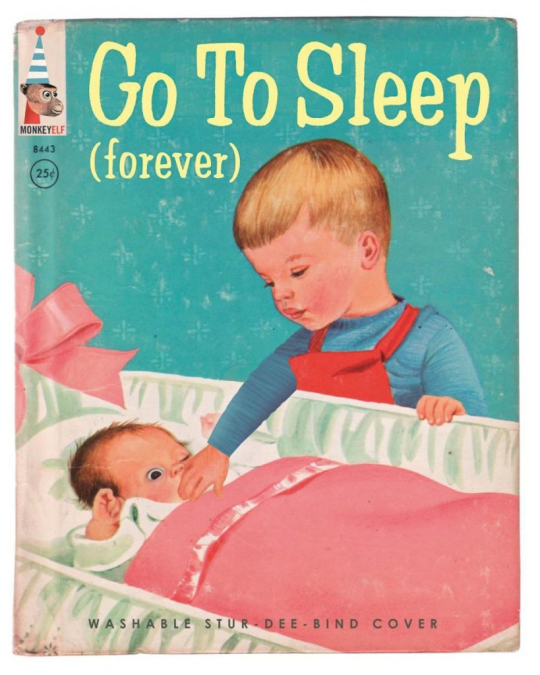

Let’s try to put it in some sort of semi-comprehensible historical context. Dark and occasionally tasteless adult-oriented satires of children’s books, television and toys have been with us about as long as media aimed specifically at the innocent set. We just can’t help ourselves. Present us with the doe-eyed lukewarm treacle of the Smurfs or Care Bears, and some of us will instinctively reach for a baseball bat. In the case of Bad Little Children’s Books, the outrage in many instances seems to be sparked less by the content than form, and the fear that the book might actually be mistaken for legitimate kidlit. So here are a handful of similar cases from the last half-century. While reactions and results differ wildly, a certain historical pattern does seem to emerge.

Ralph Bakshi’s 1972 animated feature Fritz the Cat, based on the R. Crumb character, became notorious overnight for being the first theatrically-released cartoon to receive an X rating from the MPAA. What people tend to forget is that the film received the distinction not on account of its sexual content, nor because it included characters who were overtly racist, misogynistic drug addicts who cursed a lot. The real problem was the film featured cute and fuzzy animals who were racist, misogynistic drug addicts who cursed a lot, and had sex. The MPAA board was afraid people would see the cartoon poster and stroll into the theater, family in tow, expecting the latest Disney opus. By modern standards the film should have received nothing more than an R rating, but the damning “adults only” designation was an effort to avoid any confusion. It didn’t matter. People saw the X rating and immediately concluded Bakshi had made a hardcore cartoon in a diabolical effort to corrupt the nation’s youth. Although the publicity attracted large audiences and earned the film an undeniable bit of underground cred, that same publicity did irreparable damage to Bakshi’s career. For decades afterward, even while trying to redeem himself with the family-friendly Mighty Mouse cartoon series for TV, he found himself labeled a racist, sexist pornographer determined to get America’s young people hooked on heroin—charges leveled at him mostly by people who had never seen Fritz the Cat.

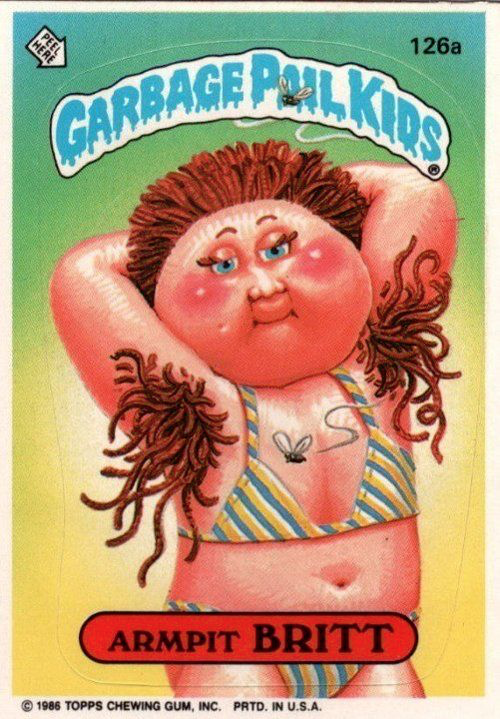

Long before he won a Pulitzer for Maus and became a regular contributor to The New Yorker, cartoonist Art Spiegelman spent twenty years working for the Topps trading card company. Among other things, he was one of the primary creative forces behind Topps’ wildly popular and wickedly subversive Wacky Packages series, which satirized American consumer products. In 1985, Topps attempted to arrange a licensing deal to release a series of trading cards based on Cabbage Patch Dolls, which were all the rage at the time. Finding licensing fees had already gone through the roof, they decided instead to release a Wacky Packages-style parody. As it happened, an unreleased Wacky Packages design called Garbage Pail Kids was already on the boards, so they ran with it.

Spiegelman and the involved artists took the basic design of the cuddly and adorable plush dolls beloved by all the world and twisted them into deranged monstrosities covered in snot, vomit, oozing sores and bugs. From the moment they hit convenience store checkout counters, the GPK stickers were outrageously popular. Although some school systems banned them as an unwelcome distraction and more than a few parents were mortified and disgusted that any sick individual would do such a horrible thing to something so innocent and cuddly, there was no organized grassroots effort to censor the stickers on moral grounds. Topps’ only real trouble came in the form of a copyright infringement suit filed by the Cabbage Patch Dolls’ creators, Original Appalachian Artworks, Inc.

Topps’ argument that what they were doing was clear and obvious parody (and therefore protected under the First Amendment) didn’t quite cut it. The suit was settled out of court, with Topps agreeing to alter the Garbage Pail Kids logo and basic character design so as to avoid any possible confusion with the original dolls. The stickers continued to come out, and went on to inspire an animated television series, a feature film, a book and an unholy array of merchandise ranging from trash cans to sunglasses. In the end, it could easily be argued that over time the Garbage Pail Kids had more of a lasting impact on the culture than their inspiration.

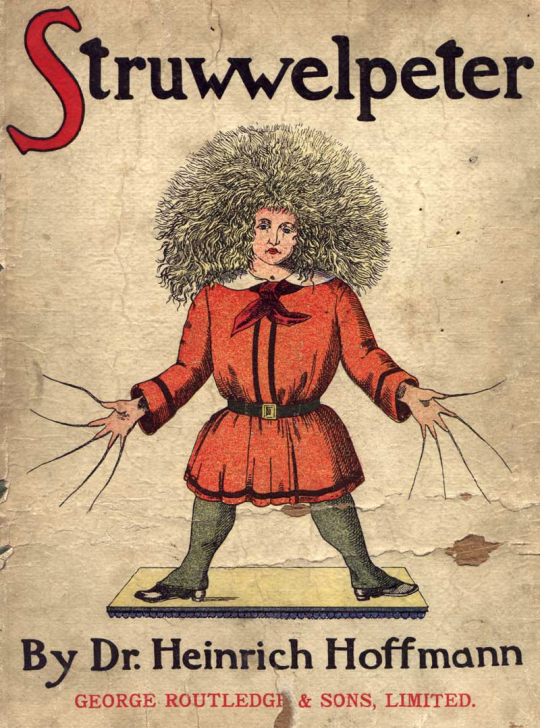

Struwwelpeter was first published in Germany in 1845. The cautionary and terrifying collection of nursery rhymes (with graphic accompanying illustrations to drive the point home) warned children that if they sucked their thumnbs, didn’t eat their dinner, didn’t clean themselves up properly, mistreated their pets or threw tantrums, a horrible fate awaited them. The book became a standard instructional volume in most German households with young children. In 1898, a similar but decidedly British version was released in England under the title Shockheaded Peter, and was nearly as popular. Nobody it seemed thought much about presenting naughty children with images of potential disfigurement or death. The book helped keep the little buggers in line.

In 1999, American indie publisher Feral House released a gorgeous new edition of Struwwelpeter, complete with new illustrations, interpretive and historical essays, and assorted bowdlerized and satirical versions of the nursery rhymes which had appeared over the years. Feral House, which had always prided itself on publishing dangerous and controversial works, soon found this simple history and analysis of a once popular if disturbing children’s book could be just as troublesome as their books by notorious British serial killer Ian Brady or the Church of Satan’s Anton LaVey.

“Yes, we had minor trouble with Struwwelpeter,” says Feral House founder and publisher Adam Parfrey. “But most of that was put to rest when bookstores simply refused to carry the book. I guess 21st century Americans are more touchy than the Germans of yore. For a while, a couple chains and many independent bookstores stopped carrying the Anton LaVey books we published after Geraldo Rivera put on those sensationalist programs about Satanism… I credit Marilyn Manson for putting an end to that crap. After he spoke out about it, so many people went into bookstores to order them that the stores saw best to get them back into their shops. Time passed, and the crazy ideas receded.”

Parfrey also sees a potential connection between the backlash Abrams suffered over Bad Little Children’s Books and the present brouhaha over what has been termed “fake news.”

“Right now there’s a good bit of madness going on with Trump-loving crazies, including Alex Jones and Infowars building up this idea that Hillary Clinton and John Podesta are torturing and killing children…and they’re pointing at Marina Abramović, too. That’s a big deal on Facebook at this instant. And anyone who poo-poos this story is being accused of covering up kiddie killing. I can see how this sort of madness can amplify into the book trade, a situation where parodies are mistaken for outright kiddie torture. Sad, isn’t it?”

As a final example, in 2010 Simon and Schuster published my book These Children Who Come at You With Knives, a collection of darkly comic fairy tales aimed at adults. Across roughly a dozen stories written in traditional fairy tale formats (though with more cursing, gratuitous gore, and uncontrolled bodily functions), assorted anthropomorphized animals, magical creatures, human children, the elderly and the dull-witted come to various terrible ends. The book received decent reviews and publicity, but there was no outcry, no controversy, and no one insisted the book be banned in order to protect the innocent. Meaning, of course, that I didn’t sell millions as a result of the hoo-hah. Christ, I’ve even heard from people who use them as bedtime stories for their own kids. Dammit! What the hell did I do wrong?

I think I made two deadly mistakes. First, despite my best efforts to the contrary, my publisher decided to release the book without illustrations, meaning it could never possibly be confused with an actual children’s book. More devastating still, I was cursed with bad timing. These Children Who Come at You With Knives was released halfway through President Obama’s first term, and while there was certainly a good deal of rancor in the air, satire was still a viable form and accepted as such, at least among the literate.

In different eras and in different ways, all the above examples were damned by a public inflicting its own preconceived notions upon works of obvious satire, insisting they be what the public believed them to be instead of what they actually were.

By the time Bad little Children’s Books was released, the world had become too ridiculous, too absurd, and as a result we lost our sense of humor. There was simply no longer any way to lampoon our chosen leaders or our own insecurities, with the world itself poised and ready to top us at every turn. In short, the book’s publication coincided with the precise moment satire breathed its last, meaning readers had no choice but to take Gackley’s work, as Parfrey points out, at face value. Lucky bastard.

Jim Knipfel is the author of Slackjaw, These Children Who Come at You with Knives, The Blow-Off, and several other books, most recently Residue (Red Hen Press, 2015). his work has appeared in New York Press, the Wall Street Journal, the Village Voice and dozens of other publications.