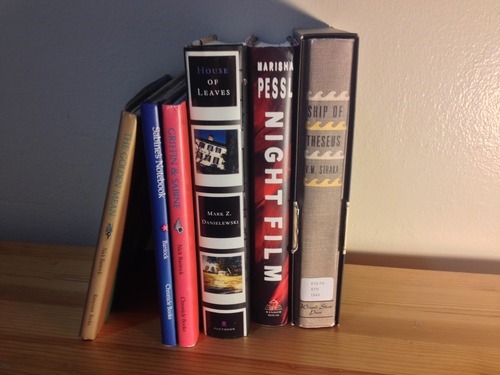

All month long, the Believer and its favorite cousin, the lovely and talented Tin House mag, are offering up a joint promotion where you can get a year-long subscription to both magazines for just $65. (Subscribe today! Here!).

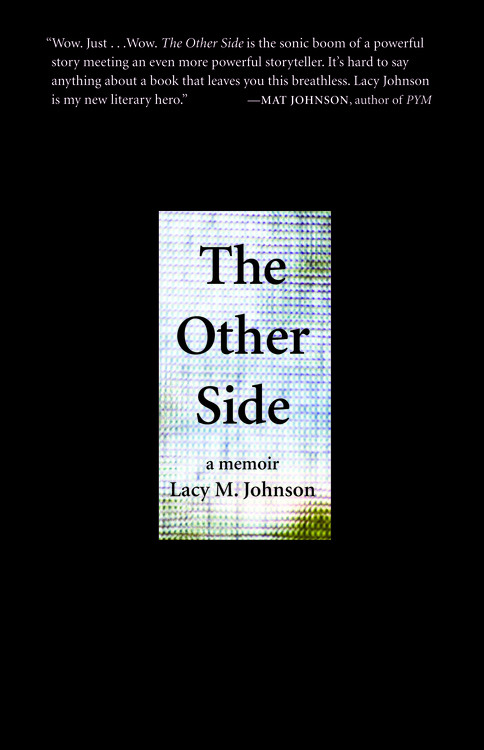

To celebrate, we’re running “The Soundproof Room,” by Lacy M. Johnson, which can also be found in the most recent issue of Tin House. It is an excerpt from Johnson’s forthcoming Tin House book, The Other Side, which can be ordered here. We hope you’ll enjoy the piece, and consider subscribing to two great magazines that look nice on the shelf right next to each other.

THE SOUNDPROOF ROOM

I won’t be coming in today

Tell me everything, he says. Start at the beginning. He does not mean the playground at the preschool with the rainbow bridge. Or the kitten tongue like sandpaper on my cheek. Or the potpourri simmering in the tiny Crock-Pot on the counter next to the jar of pennies in the kitchen. Though any of these could have been a beginning to the story I tell him. I want to see it, his little notepad, but he leaves the room to make some calls. No, I can’t call my family. No, not any of my friends. Nothing to do but to look at my feet, which are suddenly very, very absurd. Someone should cover them with shoes and socks.

He returns to lead me down a dark hallway, where every office is a room with a closed door, through a kitchen, where coffee brews and burns, out a heavy steel door to a parking lot, an unmarked car. A detective’s car. He gestures, as if to say, After you.

***

While waiting in the unmarked car on an unlit street in the dark shadow of an oak tree I realize that real cops are not at all like movie cops. Real cops are slow and fat. Their bellies, in various states of roundness, hang over their waistbands, cinched tight with braided leather belts. They do not converge on buildings with sirens blaring. They do not flash their lights or stand behind the open doors of their squad cars and aim their guns at criminals. These cops, my cops, do not wear uniforms. From the car, where I am sitting alone in the shadow of an oak tree, they look like fat men who have happened to meet on the street, who are walking together around the side of the fourplex toward the gravel parking lot, where they will find a discarded car tarp, a screen door flapping, all the lights but one turned off.

Just inside the door, they will find a dog collar, construction supplies, and a soundproofed room. I have told them what to expect. Meanwhile, waiting alone in the car under the dark shadow of an oak tree I start seeing things: no shadow is just a shadow of an oak tree. I press the heels of my palms hard into my eye sockets, sink lower into the seat. My thoughts grow smaller and race in circles. The adrenaline shakes become convulsions, become seizures, become shock. When The Detective returns, he finds me knotted into thirds on the floorboard: hardly like a woman at all.

***

At the hospital, The Detective leads me through a set of automatic sliding glass doors, not the main ones that lead to the emergency room, but another set, down the way a bit, special, for people like me. He leads me down a fluorescent-lit hallway, directly to an exam room where the overhead lights are turned off. A female officer meets me there, and a social worker who looks like she might be somebody’s grandmother. The Female Officer and The Social Worker team up with a nurse; The Detective disappears without a word. The Female Officer, The Social Worker, and The Nurse ask me to take off my clothes. They unscrew the U-bolt from my wrist. The Female Officer puts these things into a Ziploc bag named EVIDENCE.

Nice to meet you, Evidence.

The Female Officer takes pictures of my wrists and ankles. She speaks in two-syllable sentences: Oh, dear. Rape kit.

The Social Worker wants to hold my hand. No thank you, ma’am. She is, after all, not my grandmother. Her skin is loose and clammy. She asks what kind of poetry I write as The Nurse rips out fingerfuls of my pubic hair, spreads my legs, and digs inside me with a long, stiff Q-tip. Another Q-tip in my mouth for saliva. She scrapes under my fingernails with a wooden skewer and puts the scum in a plastic vial.

The Social Worker invites me to stay at her house. Or it is not her house, exactly, but a half-house for half-women like me. After the exam, The Social Worker gives me a green sweat suit in a brown paper bag. I’m supposed to dress in the bathroom. The clothes are entirely too large: a too-large hunter-green sweatshirt, a pair of too-large hunter-green sweatpants, a pair of too-large beige underwear. Like my mother wears.

The Female Officer doesn’t acknowledge that I look ridiculous when I emerge from the bathroom. She doesn’t acknowledge me at all. I know to follow her out the door, to the parking lot, her squad car. I know to hang my head; it’s the price for a ticket to the station.

Morning.

The phone call wakes my parents out of bed. Mom answers; her voice is thick, confused. She says nothing for a long time. In the background, Dad gets dressed. Yesterday’s change jingles in his pockets. His voice buckles: Say we’re on the way.

***

The Detective follows me to my new apartment in the unmarked car. He offers to come inside, to stand guard at the door, but I don’t want him to see that I have no furniture, no food in the fridge, nothing in the pantry, or the linen closet, or on the walls. I ask him to wait outside. I call my boss at the literary magazine where I am an intern and leave a message on the office voice mail: Hi there. I was kidnapped and raped last night. I won’t be coming in today. I call My Good Friend’s cell phone. I call My Older Sister’s cell phone.

While I’m in the shower, the apartment phone rings and callers leave messages on the machine: My Good Friend will stay with her boyfriend; she’s delaying her move-in date. Of course she hates to do this, but she’s just too scared to live here, with me, right now. You should find somewhere to go, she says. My Handsome Friend’s message says he heard the news from My Good Friend. He’s leaving town and doesn’t think it’s safe to tell me where to find him. The message My Older Sister leaves says she wants me to come stay at her place, which sounds better than sleeping alone in this apartment on the floor.

I pull back the curtains and see my parents standing in the parking lot talking to The Detective. My father shakes The Detective’s outstretched hand. My mother covers her chest with her arms, one hand over her mouth, a large beige purse hanging from her shoulder. She’s brought me a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and a snack-size bag of Cool Ranch Doritos. I’m not hungry, but the thought of wasting her effort makes my stomach turn.

I nibble the chips in the backseat of their car while they take me to buy a cell phone. They want to do something, to take action. With the fluorescent lights of the store, all the papers I must fill out and sign, and the windows wide open behind us, I feel dizzy enough to fall.

***

Driving to My Older Sister’s apartment, I watch the road extending behind me in the rearview mirror and try not to fall asleep. The boulevard becomes deserted intersection, becomes on-ramp, and interstate. The clusters of redbrick buildings give way to strip malls, to warehouses and truck stops, to XXX bookstores, to cultivated pastures growing in every direction: wheat-stalk brown, tree-bark brown, and corn-silk green.

My Older Sister meets me in the parking lot with tears in her eyes. Her hug is both desperate and safe. As she carries my bag up the stairs she says, You look like shit. Under any other circumstances, I’d tell her to fuck off. Today it’s a comfort. I do look exactly as I feel.

She isn’t able to get off work tonight, so she shows me how to use the cable remote, loads her handgun, puts it in my hand. It’s heavier than I would have imagined. She’ll work late tonight, but if I need anything, her next-door neighbor, The Sheriff, knows what happened. He might come by to check on me. Please try not to shoot him.

The whole time she’s gone, I watch the closed-circuit channel showing the front gate of her apartment complex. I sit in the dark with the gun in my hand and watch cars drive through the gate. I don’t know what I’m watching for, but I keep watching. A gray conversion van looks suspicious. I peer through a crack in the blinds.

I don’t eat. I don’t sleep. Even after My Older Sister comes home, offers me a beer, falls asleep with her arm around my body in the bed, I fix my eyes on the dark and wait.

And wait.

And wait.

***

Schrödinger’s famous thought experiment instructs us to imagine that a cat is trapped in a steel chamber along with a tiny bit of radioactive substance—so tiny that there is equal probability that one atom of the substance will or will not decay in the course of an hour. If one of the atoms of this substance happens to decay, a device inside the chamber will shatter a small flask of hydrocyanic acid, killing the cat. If it does not decay, the cat survives. It is impossible to know, with certainty, whether the cat is alive or dead at any given moment without looking inside the steel chamber, since there is equal probability of either outcome. And because both outcomes exist in equal probability, this creates a paradox: the cat is both alive and dead to the universe outside the chamber. These two outcomes continue to coexist only until someone opens the chamber and looks inside, causing those two possible outcomes to collapse and become one.

***

The form itself is simple: my name, the police records I am requesting, the case number, the dollar amount I am willing to pay for copying fees. These fees can be waived if the request in some way serves the public interest. I was the victim in this case, I write on the form. I can think of no way in which this serves the public interest, but I would like to see the files anyway.

A sergeant in the Public Relations Unit responds to my request within the week. After thirteen years the case remains open and The Sergeant needs to consult with the city legal advisor prior to making a decision, Since, you know, it involves a serious active case. Three weeks later, after speaking with the law department, as well as with the lead investigator, The Sergeant sends me a PDF file along with a polite offer of further assistance.

At first I decide I won’t open it while I’m at home—not while there is laundry to be washed and folded, not while there is food to be cooked, and children to be bathed and fed. I’ll wait until my trip to upstate New York in early summer. But then I spend whole mornings distracted by possibilities. Is the cat alive or dead? After two days, when my children are at school and My Husband is out of town, I open the file, thinking I’ll only look a little bit. Just a little. Just a peek.

***

The evidence file contains eighty-five pages of police reports, including an inventory of items collected from the crime scene: “chain,” “brown envelope with handwritten notes,” “two leather belts tied together,” and “film neg[atives].” It does not describe whether there are images on those negatives. It does not describe the results of any laboratory tests or the e-mails and correspondence I sent to and received from The Suspect, though they are mentioned. There are no facsimiles or transcripts of conversations I had with the prosecutors or the police. The file does not contain copies of warrants, though it lists the complete set of charges filed on my behalf.

The first half of the file contains reports of the same events during the same time period on the same day, each report from the perspective of a different officer, each report in part relating the story I told to one officer or another. The writers do not reflect. They do not sympathize. They express no pity or outrage or disgust. Each report simply records my story, but it is not my story, though it is the same version of the story I would tell. Almost word for word. Like something I memorized long ago and can still perform by heart.

***

And yet, as I read through the evidence file, I see things I don’t remember. Like how, according to the police reports, it was The Female Officer, not The Detective, who came out to meet me at the station, and The Female Officer also drove me to the apartment I’d escaped, and then to the hospital, and then back to the station. But in my memory, this role is so clearly played by The Detective, a man who looks vaguely like my uncle.

I try to remember my two fists pressed against the glass separating me from the two female dispatchers, the locked beige door to my left. I remember it opening, and I try to see The Female Officer’s face instead of The Detective’s face. I try to remember her dark-blue uniform, every corner pressed and in its place, the black belt with its gold buckle, the gold buttons, every hair on her head tied back into a neat bun. I can see the long hallway behind her. I can see the little notepad. And the office. And the black telephone. The carpet in the hallway is beige, darker in the middle than where it meets the walls at the edges. But when I try to see The Female Officer instead of The Detective the whole image starts to collapse, and then there is neither a female officer nor a male detective opening the locked beige door. There is no opening the door.

Until I looked through the police reports, I didn’t know that while I was waiting in the unmarked police car outside the basement apartment, one of the officers called the owner of the building, a man I knew as the bartender at our favorite dive downtown. He came to the apartment, maybe while I was waiting outside, and confirmed that he owned the building, and that his tenant, the same person as The Suspect, was a friend. After the landlord refused to tell the police where they could find The Suspect, and after he tried several times to call his tenant, he was arrested for obstructing a government operation. He was later processed and transported to the county jail.

I also didn’t know that, in the early days of the investigation, one of The Suspect’s former students showed up at the police department, admitting that The Suspect paid him $100 to help him build the soundproofed room. They spent an entire weekend working on it together. The owner of the building let them use his pickup truck to haul supplies and stopped by periodically to check on the progress. At one point he brought fresh watermelon and cantaloupe for them to eat. The student said he remembered that his former instructor had paid for everything with an envelope full of cash.

Until I looked through the police reports, I didn’t know that on July 5, the night of the kidnapping, The Suspect called the Mall 4 Theatres, asking if My Handsome Friend was working that evening. My Handsome Friend had told his bosses and fellow employees that some psycho might come to the theater looking for him, and asked them not to give out any information about him over the phone or in person, or to let on that he still worked at the theater. My Handsome Friend told police that for six months The Suspect had been following him, driving past his house and the building where he worked, because he thought we were having an affair. My Handsome Friend told police he believed that The Suspect might harm him. He didn’t know what The Suspect might do to him.

I also didn’t know that, after the story was reported on the news, people phoned in to the Crime Stoppers hotline to offer information they had about the case. One woman, an employee at a big-box hardware store, had helped The Suspect select glue for the Styrofoam he would later use to build what he called “a sound studio.” One man, who worked at a sound supply shop on the business loop, said The Suspect had asked him how to build a soundproofed room insulated enough to muffle a woman’s screams. For making movies, The Suspect had said.

***

According to the police reports, bank records reflect that sometime after 5:00 PM on July 5, 2000, The Suspect withdrew $750 from his checking account at an ATM only blocks from the building where I worked. Which means he may have gone to the ATM as early as 5:01 PM, moments before he approached me in the parking lot outside the building where I worked. Or as late as 11:59 PM, after he returned to the apartment where he had built the soundproofed room and discovered that I’d escaped.

Early the following morning, before I’d called my parents or returned to my apartment to shower and pack, before the nurse had finished searching the surfaces and cavities of my body for evidence, he withdrew another $750 from an ATM at a gas station at the intersection of two highways 150 miles away to the west and north by interstate. From that ATM he drove fifty-two miles south and parked his rental car on a street in the downtown business district of one of the few actual cities in the state, where it would be discovered by an officer from the Stolen Auto Division a month later.

On July 7, two days after the kidnapping, he purchased an airline ticket to León, Guanajuato, Mexico, at the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport. After arriving in Mexico, after passing without incident through immigration and customs, he walked to the ticket desk and purchased an airline ticket to Porlamar, the largest city on Margarita Island, just off the coast of Venezuela. He got off the plane in Santiago Mariño Caribbean International Airport that afternoon and withdrew $1,200 from an ATM. That evening, just before the bank froze his account, just before I learned to accept the weight of my sister’s gun in my hand, one final debit for $29.56 posted to his checking account, from a restaurant at one of the island’s resorts.

***

One police report describes how, on July 12, one week after the kidnapping, at 9:10 AM, The Suspect called his stepfather at his home in southern Missouri: a cabin just this side of a shack, the only building I remember now along the gravel road stretching across a heavily wooded hilltop, where it seemed a fresh buck was always swinging from a tree, the red gash of its belly gaping open. I remember eating stewed squirrel in the kitchen at a card table, loading the woodstove in the cramped living room, watching the clouds of my breath from a mattress on the floor in the only bedroom. I don’t remember seeing a phone. But it rang three times, the report says, before his stepfather picked up. He asked, Where are you? The Suspect wouldn’t say. They talked briefly about the case. Yes, I did get her, The Suspect admitted, but he denied the allegations of rape. If you want to call Lacy, go ahead, he said. His stepfather asked again, Where are you? The Suspect refused to say, but then started talking to another person near the phone in Spanish. At 10:00 AM on July 12, his stepfather called The Detective to report the call. He said The Suspect seemed very upset about the media exposure on the case.

***

In another report, The Detective writes how, on July 17, twelve days after the kidnapping, he and another officer came to my apartment to talk to me about the case. I told them that The Suspect and I met while I was a student in his Spanish class at the university. I told them that I had been trying to break up with him for some time, for lots of reasons, but mostly because he had raped me on more than one occasion. I told the officers that when I finally did break up with him, six weeks earlier, he did not take it well.

The Detective writes that I told him and the other officer that The Suspect had been arrested before, in Denmark. I remember telling them the version of the story I was told: he was married for years and years to a Danish woman, they had two children together, and after they split up, he took the children to the United States, forgetting to tell her that he was leaving the country. The report doesn’t mention how the officers looked at each other when I said this, how they might have wanted to ask more questions about this version of his story but didn’t. The Detective writes that I said that the man kept the children in the United States while his ex-wife called and called and eventually convinced him to come home. She told him she wanted to get back together. A trick, I told the officers. He was arrested as he got off the plane, and while he awaited trial, his ex-wife flew to the United States to retrieve her children. The Detective writes that I told them that the ex-wife has avoided The Suspect since that time. They have no contact. She gets no child support.

The next report in the file describes a fax The Detective received from his liaison at Interpol, who located a record in the Interpol Criminal Register. The Suspect was convicted in Denmark in 1995 of depriving parental custody rights to his ex-wife and received a suspended sentence of sixty days in prison. Earlier the same year he had been arrested for rape, though the crime was dropped due to lack of evidence. The Detective speculates in his report that the victim in this dropped case is The Suspect’s ex-wife, current residence unknown.

***

In the final police report, dated August 14, 2000, I am identified as Lacy Johnson: VICTIM. I read this and feel certain it is true. I see myself as the officers saw me: someone who phones the police station to report a suspicious number on her caller ID. I am a subject to be questioned, a story to be investigated, a set of illegal acts that were perpetrated by a suspect who has disappeared.

And yet, when I close the file, I remember how the truth is more complicated than this. I remember, for example, making choices. I look into his eyes while I undress. When it is done he apologizes and finds me something to eat. I tell him everything is fine, just fine, and stroke his hair while he cries into my lap. He begs me to come back. Outside, in the hallway, his rifle leans against the wall. At any moment, he may or may not kill me. I remember how the two possibilities can coexist: I’m both alive and dead in every room but this.